Search, and ye shall... maybe?

The Economics of Matchmaking Part I: Search Theory

1. Search Quest

Knights in pursuit of the Holy Grail. A fallen hero seeks redemption. A recluse, jaded by life’s trials, unexpectedly finds romance.

All great stories center on a search. A quest for this elusive ‘thing’ that can change everything.

So it is with our lives.

Fresh grads hunt for jobs. Newlyweds shop for overpriced real estate. You’re trying to find answers, while I go look for trouble.

But the search, like all quests, comes with risks. The thing we want might not exist. And if it does, it's nothing like we imagined. Or, we realize too late it was never right to begin with.

Despite all the unknowns, there's a logic to this quest. An economic structure that underpins our search.

2. Stranger than Frictions

A core doctrine of Economic theory is that markets coordinate everything. Buyers find their sellers. Supply equals demand. People agree on the price. The deal is done.

In reality, it is not that smooth. Sellers and buyers have to find each other. Startups scramble to find funding. Investors scout diligently for promising businesses. Firms struggle to fill vacancies despite a flood of applicants. Your friend that’s still single doomswipe for that perfect match. There are obstacles to search—frictions. The delays, disagreements and dead-ends. That makes search a trying process.

Search Theory was developed by economists to better understand these frictions. To model how people, like you and me, make our choice when we don’t have all the facts (information asymmetries and uncertainties) and face a variety of costs.

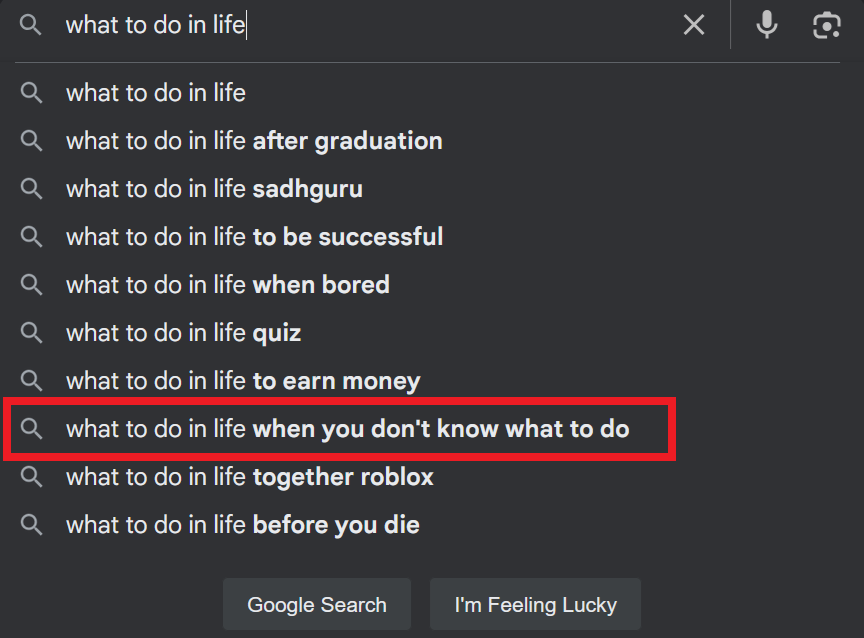

We live in an age of relative abundance. There’s a hoard of information on the internet. Engines like Google or even ChatGPT may provide some help, so do job listings. But that abundance can be overwhelming.

Well-meaning friends would then say, there’s plenty of fish in the sea. You’ll catch something.

But the ocean is polluted. There’s too much junk out there. Misinformation is rife. People misrepresent themselves, they lie on their CV. They say they’re 6’5” but barely 5’9”.

Then there’s overfishing. Competition is fierce, the pool of great candidates shrinks fast. All the good ones always seem to be already spoken for. Some firms behave aggressively, snapping up talent and hoarding them away from the competition.

Let’s not deny climate change. The Ecosystem evolves with time. Economic conditions are always on the move. Industries are disrupted. Cultures adapt. Preferences change. A desirable option yesterday might not be useful tomorrow. What once was your soulmate, might become a living nightmare.

There’s a cost to search. Real costs.

The price you pay to access better info on job sites or dating apps. The time spent searching. Time spent weighing options and decisions.

The opportunity costs of searching itself. Foregoing the choice you have in front of you, with all the benefits of an income and security, for the next one’s potential option value.

Worse, the cost of being on the wrong path. Because you cannot turn back once you commit. Time is irreversible. You can not redo.

There’s also the emotional tax. The mounting frustrations. Be it from a string of bad dates. One horrible interview after the other. Running into dead ends. The cold indifference from being ghosted by recruiters. The crushing rejection from someone you wanted to spend your life with.

The sheer exhaustion of having to put yourself out there.

Again.

And again.

And again.

3. Do you have a reservation?

We don't have to search blindly. Getting needlessly lost in the search. There are strategies that can help us on our journey. Think of them as SEOs (Search Effort Optimization).

For example, someone looking for work would not consider anything less than what they currently earn. That would be unacceptable. Economists call it the reservation wage. Unemployment persists because, sometimes, the jobs available do not meet that reservation.

In everyday life, we don’t just look for prices or a salary. With jobs, people today ask for remote work. Medical benefits. Paid leaves and childcare. Locations and accessibility. Company fit and professional development.

The flipside: we don’t always know what we want before we start searching. “You’ll know it when you see it.” Fantastic advice. Tells you absolutely nothing on how to start.

We set standards–a checklist that filters out anything we won’t accept. Be more deliberate in our search. Call it the reservation criteria.

Another reason for setting this reservation is so you don’t get captured by one feature above all the others. You might be interested in taking the high-powered job that pays 30% more, but it demands 80-hour weeks from you. A charming 10/10 can blind you to red flags.

This reservation is our starting point, but your expectations shouldn’t be set in stone. You adapt as you go out into the market. You gather information. Explore your options. In the process, you learn what you really like, what you definitely don’t like. Perhaps knowing what your true worth might be. You learn what you can offer the world and what the world can offer you in return.

If the market surprises you with better opportunities, you might just raise the bar. At the risk of prolonging the search.

Bad experiences, however, may cause you to get a little desperate—you lower your bar and just settle for less. Or you recalibrate expectations. Not all compromises are failures. It’s just being real.

4. What’s your (stop) sign?

So, how long should we spend looking? How do we know we made the best choice? What are the chances of meeting the best of all possible candidates?

The answers, or a way of solving them, lie at the root of search theory.

Search theory was derived from this broader class of math problems known as optimal stopping. i.e. selecting the best time to stop searching and make up your mind.

Stop too early, you might just miss the best one a few steps away.

Stop too late, you still rack up mileage on search, possibly have passed on the best option, and never even know it.

If you don’t make a choice and commit, you can not advance.

One of the well-studied topics on optimal stopping is the secretary problem (for the more romantically inclined, the marriage problem).

The set up:

Your company wants to hire a secretary, and you're tasked with finding the best candidate, and offering them the job.

You have N applicants

You interview them sequentially, in random order.

You either accept them or reject them. No Recall.

Accept and the search stops.

Reject you move on to the next candidate.

The optimal strategy is known as the 37% rule.

Step one: Look.

From 100 potential candidates. You interview the first 37. You don’t commit to hiring. You’re there to just learn about the quality of the available options. You build up your reservation criteria.

Step two: Leap.

For the remaining candidates, you reject everyone else that doesn’t meet those criteria. Offer the job immediately to the candidate that is better than the first 37.

The odds of picking the right candidate is also 37 percent! In 100 possible permutations, you’ll pick the best candidate 37 times.

It’s not great. it’s less than 50-50. But it’s a strategy, better than gambling aimlessly.

You can apply this to other problems involving a search. Like project management, research, scrolling Netflix. It doesn’t have to be N candidates, or options. It can be T for time. Spend the first 37% of the budgeted time ( be it 12 weeks, one month whatever) just gathering information. Then the rest of the time, use the info to execute on the project, write the paper or pick a damn movie to watch.

5. Optimal Romance

In 1612, Johannes Kepler, legendary astronomer, lost his first wife to an illness.

Five stages of grief later, he considered remarrying. He asked his friends and peers to introduce him to women looking to marry. They presented him with 11 women to court.

With the rigour of a scientist he interviewed them one by one. We know this story because historians found Kepler’s notes. He was that meticulous!

He passed on the first four, though he liked the fourth. 37% of 11 is ~4. Right on schedule. Because after meeting the fifth, a lady named Susanna Reutinger, he was truly enamoured. Kepler found his optimal choice. He wanted to ask for her hand in marriage there and then.

However, his peers got hold of him before he could pop the question. They pressured him to consider the fourth instead. Citing her family background and status. He relented, and popped the question. Lady 4 turned him down, because he took too long to get back to her.

Kepler then went back to his optimal choice, Susanna. He asked for her hand, and the planets aligned. She said yes. :’)

The lesson here?

Trust the math. Don’t cave to peer pressure.

6. Feeling Lucky?

Life is far more flexible than we give it credit for. You can reverse some decisions. This actually improves your odds, at a cost.

Life is also more ruthless too. You can be rejected. Depending on how likely they are to say no to you, your odds shrink far below 30%.

In professional settings, there’s usually a good signal to count on. Like chartered and secretaries. University transcripts. Priors and referrals. Making the information far more reliable. Affording you a much smaller number of interviews but with greater chance of picking the best candidate.

I’ve left out a few things.

One being that luck plays an outsized part. Not the luck that’s quantifiable like odds. But the kind of luck that just changes everything and sets you up on an altogether different path. The things that just fall in front of you, that you did not even look for. Like an instant spark when eyes make contact, or the next global crisis.

I’ve also presented search as a one-sided process. Leaving out an important dimension to the quest: You can choose but you must be chosen in return!

Then, and only then, does a match make. But that’s a blog post for another time.

…

Whatever it is. Whether it is finding a place to stay. Maybe in a search for a partner or even a purpose in life. We’re all searchers. You are not alone.

May you find what you are searching for, and I hope it finds you too.

Refs, Recs & Inspos

Algorithms to Live By (Brian Christian, Tom Griffiths)

Optimal Stopping (Brian Christian)

Who Solved the Secretary Problem? (Thomas S. Ferguson)

Search-Theoretic Models of the Labor Market: A Survey (Rogerson, Shimer & Wright)

Solid article. I think a big insight for me with my searching issues was that, like tasks, you gotta prioritize.

Some things, like replacing socks, doesn’t need to be optimized and can even be automated or put on a subscription plan. Or just get a bunch at Target.

Others, like picking out a birthday gift for your child, could be delegated but why give up the joy and connection-building potential?

I say, Eisenhower Matrix it, but instead of going by “Urgent/Non-urgent” vs “Important/un-important” I would replace the latter axis with “Rewarding/Not Rewarding”