Make me a matchmaking market

The Economics of Matchmaking Part IV: Market Design

This is part 4 of a series on the Economics of Matchmaking. Read up on the previous entries:

here, here and here.

Encountering Chances

Life’s defining moments often feel like a stroke of divine serendipity. Like the career that consumes our days, or the partner we share our nights with. Like we just lucked into that job or relationship.

But that serendipity is an illusion. Fate is merely downstream of the hidden architecture of markets.

Markets are not just these grand abstract bazaars, where people buy and sell things. They are structures built on institutions, social norms and the silent authority of the law. They are the invisible forces that make seemingly random collisions into meaningful exchanges.

Economists are not just passive observers of the markets. They are its architects too. Because without structures, markets can drift and unravel into chaos.

Design Intervention

In the 1900s, hospitals competed ferociously for doctors. The supply of medical graduates was small, and there were a lot of hospitals with vacancies.

These hospitals began headhunting for top talent, recruiting these would-be doctors months before they graduate. The competition intensified. Some hospitals began sending earlier offers to students. Years ahead of graduation, before these students ever held a scapel. This was a problem, because if hospitals wanted to cut through all that mess, they’d lock in recruits right from kindergarten!

The schools tried to put a stop to this by only publishing transcripts and letters of recommendation closer to graduation dates. This only changed the nature of the competition.

Hospitals sent exploding offers, take-it-or-leave-it type of deals, to medical graduates. Those offers, initially, would expire after a couple of weeks. The ensuing competition squeezed it to a matter of hours. Forcing some 20-somethings to commit the next five years of their lives over a lunch break.

This was unsustainable. The market for future doctors was unraveling into something more like a Black Friday sales frenzy.

To stop this frantic brawl, an intervention was designed. Enter the Boston pool, aka the ‘Match’.

The Match was an algorithm that would match hospitals offering programs to students applying for those programs. This algorithm served as a clearinghouse to ensure the market was stable.

After some negotiations, the first ‘Match’ was run in 1952. It was a return to civilization. A better alternative to the frenzy. Everyone was (mostly) happy. It lives on today as the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP).

Stable Takes

This market disaster of hospitals and graduates is known as the stable matching problem.

Imagine a crowded ballroom where everyone is looking for a dance partner. People pair up, but if someone sees a partner they like better, and that partner likes them back, they’ll ditch their current partners.

Alice is with Bob, but she spots Jasper. Jasper too would also rather be with Alice than his current partner. They will ditch their dates and elope instead. This reshuffling is what happened to the hospitals and graduates.

This is instability.

What we want is a market where no such chaos can occur.

In game theory, a match is stable if there isn’t a single pair of people out there who would both ditch their current partners to be with each other.

To achieve this, the markets must first be thick—where there are enough participants on each side to transact. They don’t have to take the first deal they get. The medical market failed because it was thin. Hospitals were desperate because there was just not enough talent to recruit from.

But thickness alone can lead to congestion. Like the name implies, congestion is a traffic jam of information and exchanges. A well-designed market must have the space to let people digest information. Give them time to process and explore their options.

Crucially, stable markets must induce honesty. When the rules make truthfulness a profitable strategy, participants no longer need to game the market. They can reveal their true preferences, and simply become who they are.

Game, Set and Match

One mechanism that can engineer stable matchings is the Gale-Shapley Algorithm.

In the original setting, Gale-Shapley takes two separate groups—usually men and women—and pairs them through a process of elimination.

The algorithm’s promise is that it will find a stable match. It does this by imposing order through deferred acceptance: The men propose, but the women don’t say “Yes”—they say “Maybe.”

To see how this works, we’ll have to enter A Midsummer Night’s Dream:

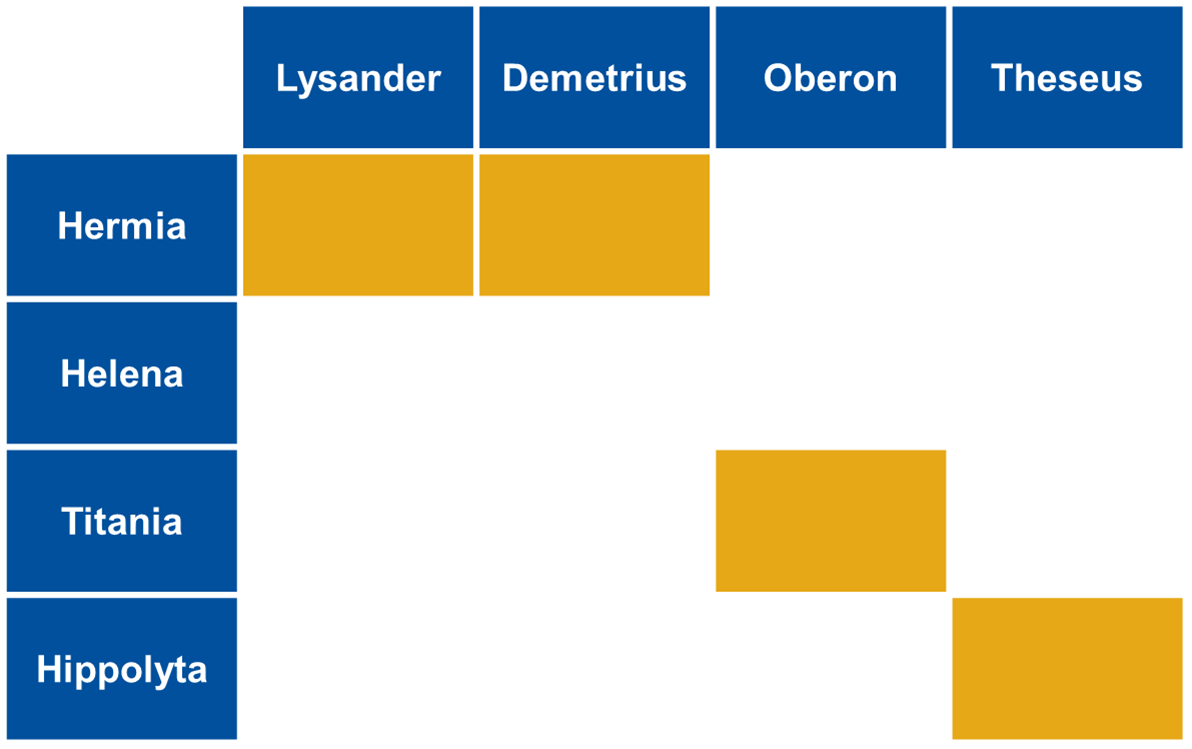

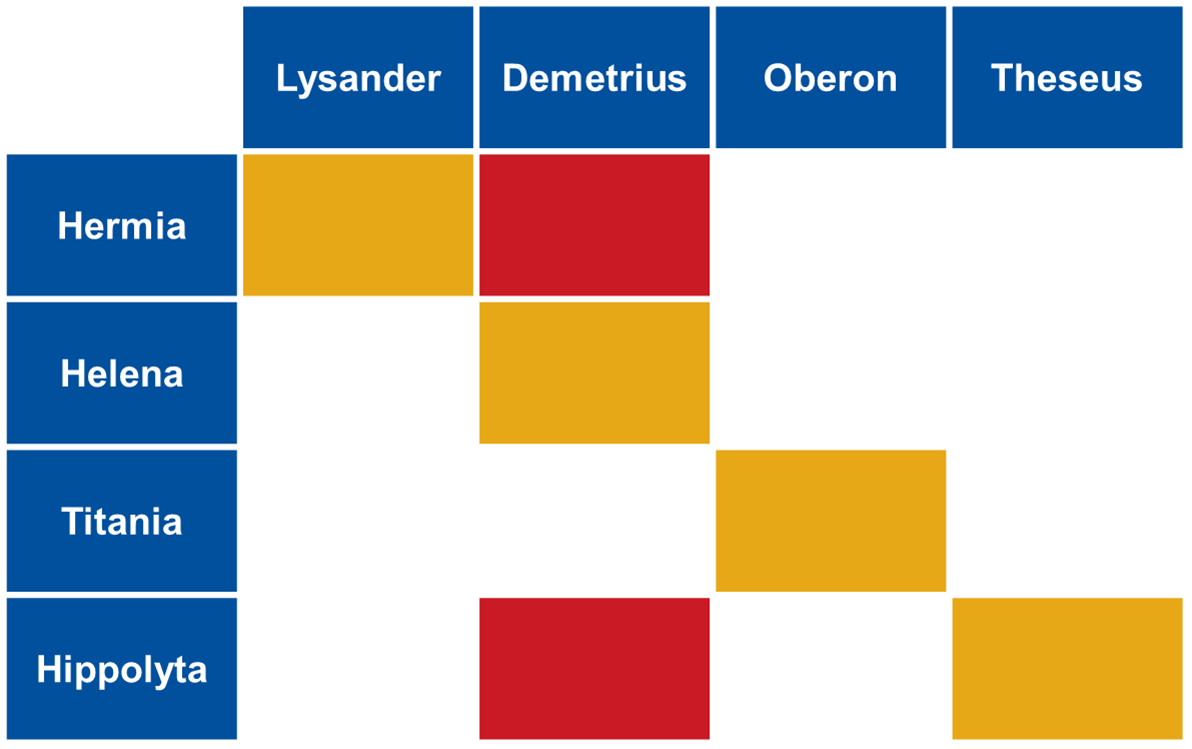

The Setup: Lysander and Demetrius both rank Hermia as their #1. Theseus and Oberon have their eye on their queens, Hippolyta and Titania.

The Algorithm takes their ranked order lists, and begins sorting pairs.

Round 1

The men all propose to their first choice. Hermia receives two offers.

In another market, she’d have to pick one instantly. Under Gale-Shapley, she says “Maybe.” She holds Lysander (her preferred choice) but rejects Demetrius. Titania and Hippolyta hold their proposals with a maybe too.

Round 2

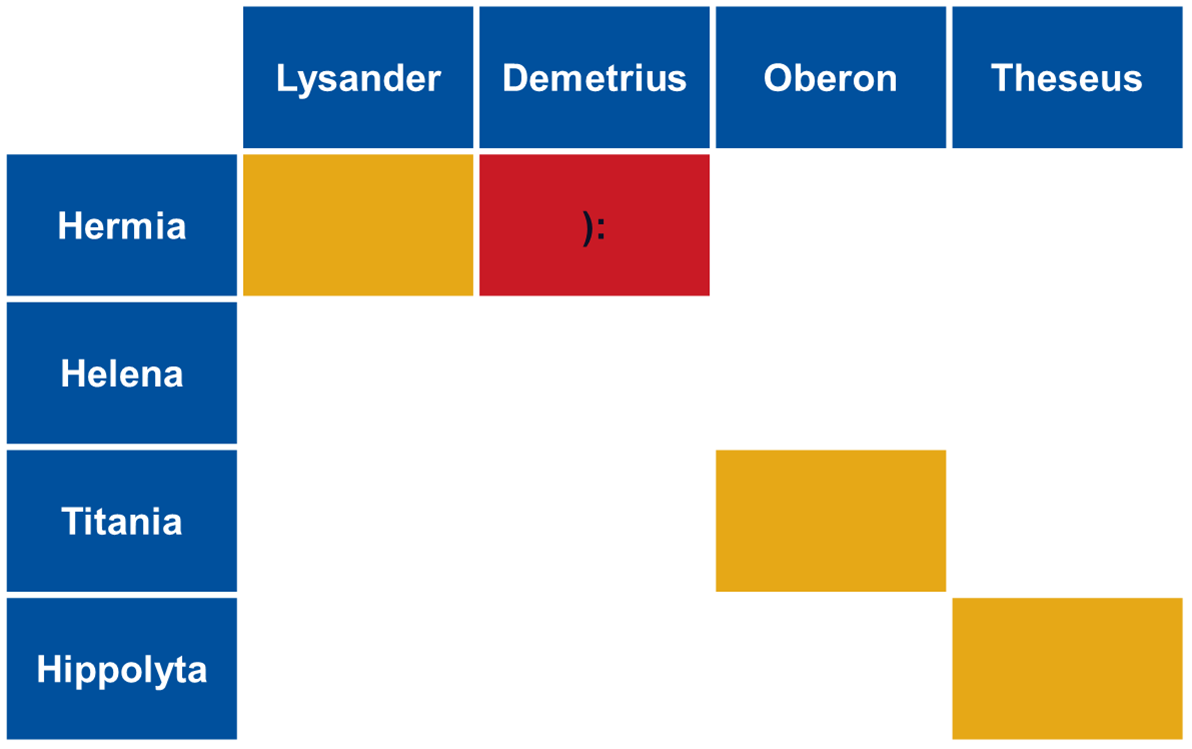

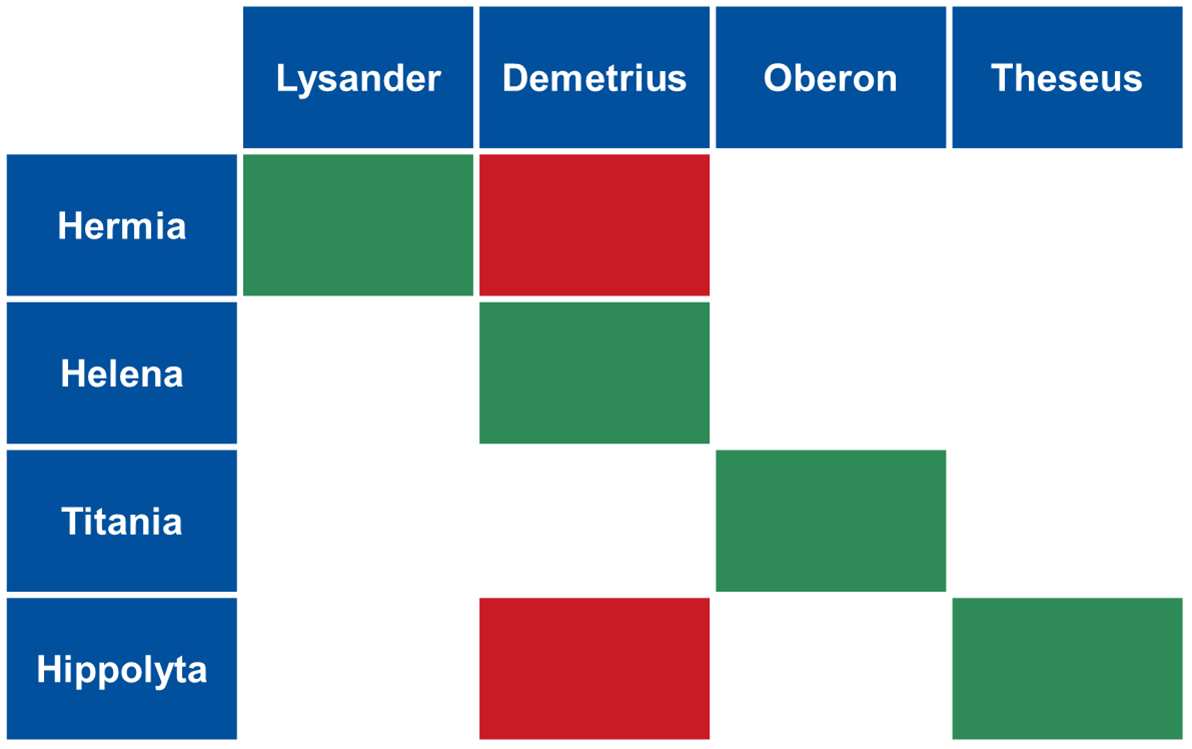

Demetrius, the “odd man out,” moves to his #2, Hippolyta.

But Hippolyta already holds an offer. She likes Theseus best. So she too rejects Demetrius. Tough.

Round 3

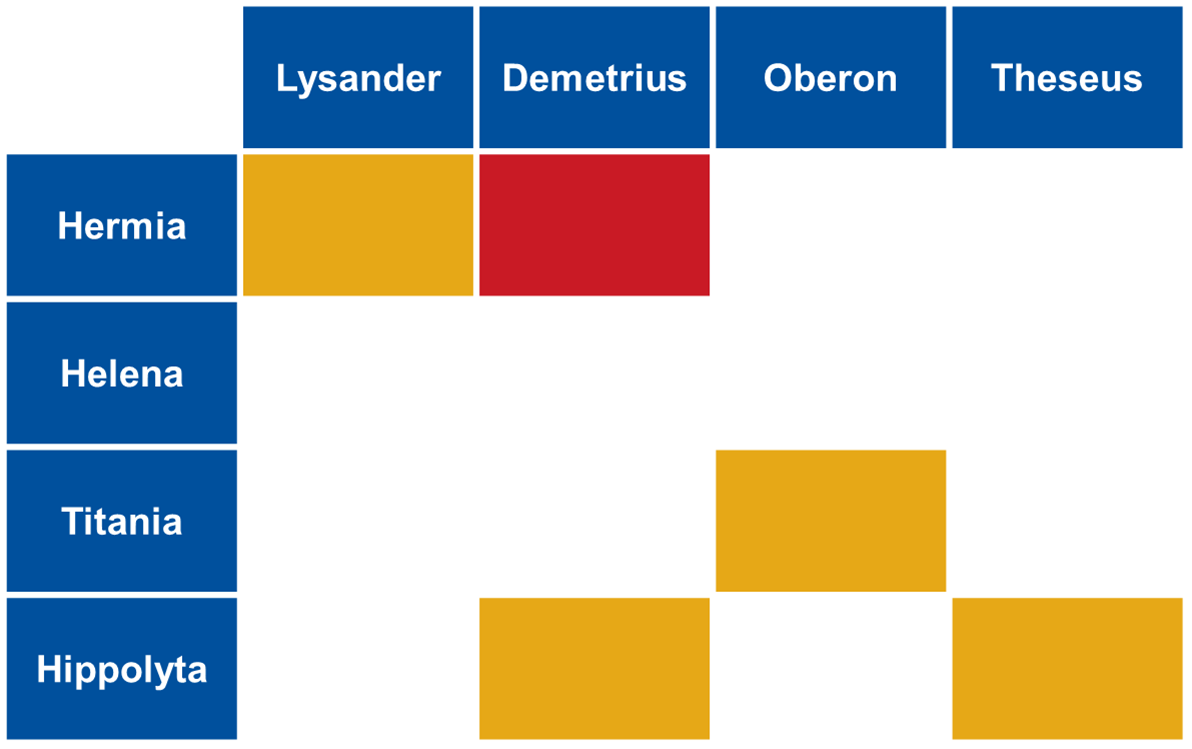

Demetrius moves down his list and now proposes to Helena.

Helena has no other offers, so she holds him tentatively.

The Magic: Because acceptance is deferred, the market doesn’t unravel. The “Maybe” is the buffer. It allows the men to make their pitch, and the women to consider without locking in the decision.

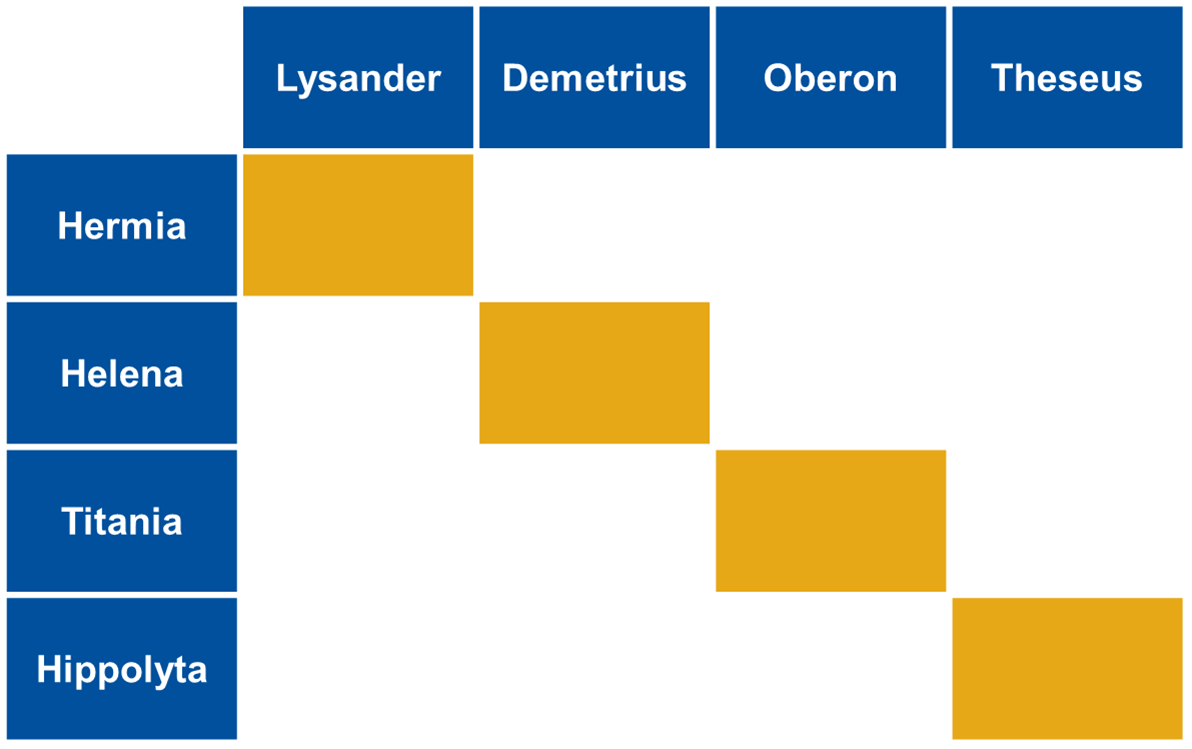

The rounds continue until every man has a proposal that isn’t rejected. Then and only then, ‘Maybe’ becomes ‘Yes’!

The original NRMP approximates this deferred acceptance algorithm, with a twist.

Requests for Proposals

a. First mover’s advantage

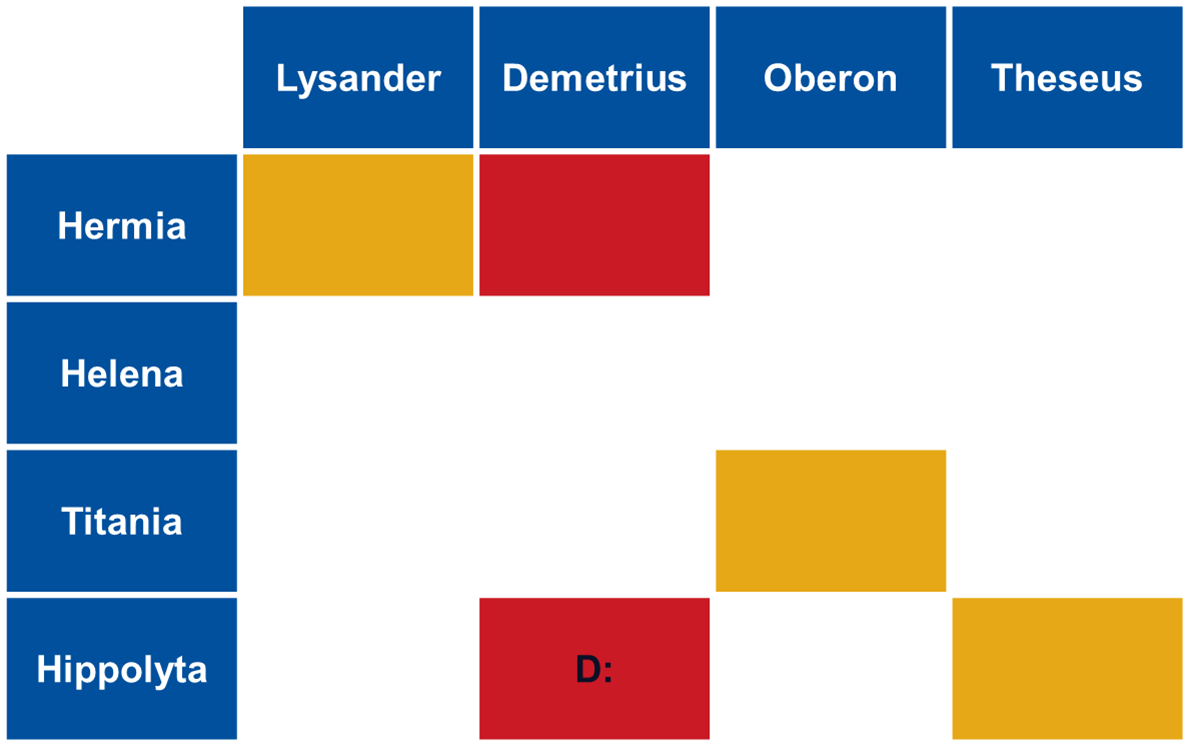

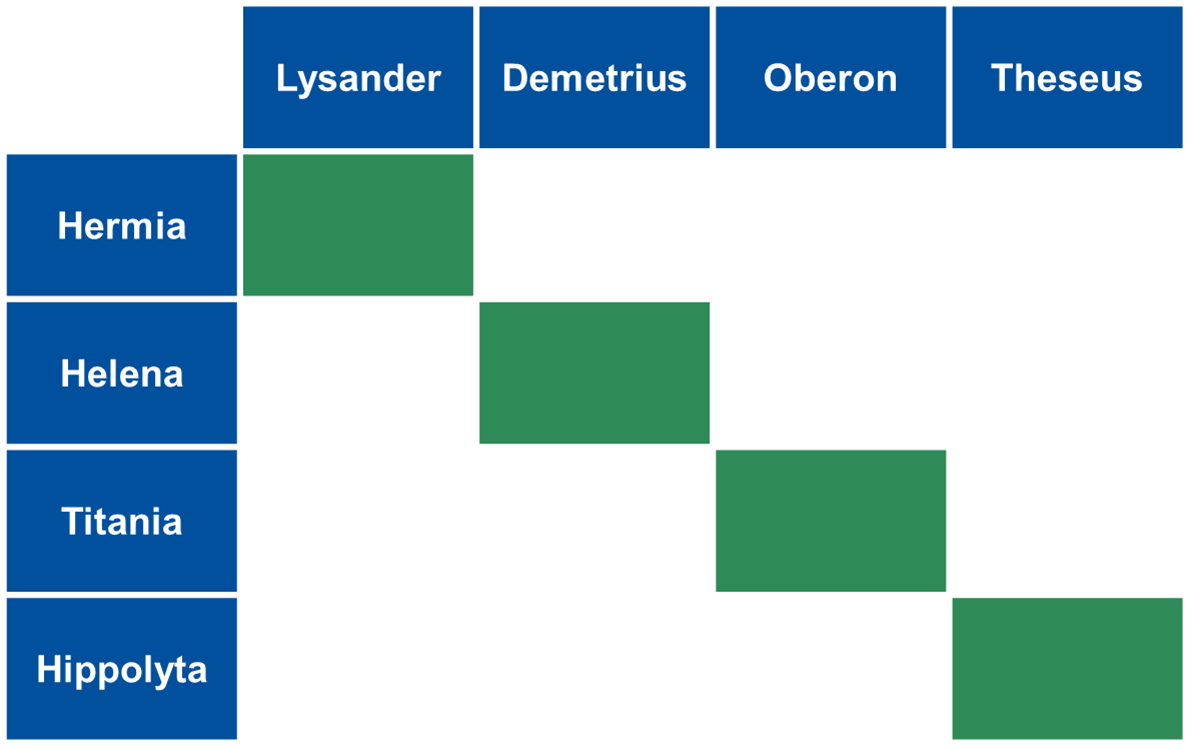

Let’s suppose the game gets flipped. The women do the proposing now.

Within the first round, all the women made their first offers. And no one gets rejected. The algorithm stops right there.

The algorithm is Proposer-Optimal, but Proposee-Pessimal. The side that the algorithm leads with—the proposer—ends up with the best possible match. The side that waits for offers—the proposee—ends up at the mercy of whoever moves first.

For decades, the NRMP was mathematically tilted in favor of the hospitals. It wasn’t until the 1990s, that the algorithm was flipped to make students the proposers.

It was a win, but a hollow one. Because by then, the market has changed. The supply of students vastly outnumber the vacancies at hospitals. It was a policy change in conditions that made it less meaningful.

b. Honesty, the best policy

There’s another key feature to the algorithm. For the proposers, it is strategy-proof. It cannot be gamed.

It’s already working in the proposer’s favour. Why lie about their choices? Demetrius cannot rank Hippolyta as number one and expect to get matched to Hermia over Lysander.

For the proposees, there is some room for exploiting the algorithm. But this requires near-perfect knowledge of all the players and their preferences too. In effect, honesty is still the best policy.

Don’t hate the game. Don’t hate the other players. If you end up with someone you don’t like, you’ve only played yourself.

Optimal, but not Perfect

Optimal is a technical term. It means we have achieved the best possible assignment given everyone’s choices and constraints.

Even if a match is stable, it might not be either person’s absolute dream match. No algorithm can account for the ever-changing human desires, or the mind-numbing bureaucracy of hospital administrations. The machine only handles the arrangements.

Making the relationship work, or calling it off, is entirely up to you.

Addendum

Variations of matching algorithms have been applied to different fields where coordination across thousands, even millions, of participants has to be designed.

School placements

Google’s early Search + Ads algorithm was akin to stable matching.

Refs, Recs and Inspos

Sheriff of Sodium’s series on The Match